Squeezed Dry

June, 2022

If experience makes the best teacher, our lesson began in the summer of 2018 when we were going to camp in Yosemite National Park. The park had to temporarily close due to the Ferguson Fire nearby, so we rerouted 200 miles to the south. The air in our new location was still filled with smoke from the fire.

We thought to ourselves, given all the trips we have made out West over the years, we were bound to be impacted by a fire eventually and this was it. Little did we know we were experiencing something that was to become all-too common for us and for too many other people living in or visiting the mountains.

Too Many to Count

We have never been surrounded by so many fires and driven through such heavy smoke for so long as we did two years later in the summer of 2020. This was the summer when hundreds of fires engulfed the West.

Enjoying Mount Baker at sunset.

For us, it started at the base of Mount Baker in northern Washington. We enjoyed the pristine view of the mountain as the setting sun gave it a soft, warm glow. By dawn, nearby fires had greatly expanded, and smoke quickly moved in overnight, catching us by surprise. The mountain, and all that surrounded it, were completely hidden from view.

We decided to make our way south, hoping for a break. After several detours due to new fires popping up along the way, we camped under smoky skies on the Pacific Coast in Astoria, Oregon. We soon decided to seek clear air by driving east. There was no point heading into California as too many of the roads were at risk of being impassable due to fires.

This is what the drive across Oregon looked like.

Much of the time driving through Oregon, visibility was at most one-half mile. We didn’t see blue skies until we were on the other side of Salt Lake City, some 900 miles away.

There’s Always Next Year

In the summer of 2021, we stopped for a quick dinner in the northern California mountain town of Susanville. Smoke from the nearby Dixie Fire was so heavy we had difficulty breathing as soon as we opened the van door. The entire city had just regained power shortly before we arrived, having gone without electricity for a week due to the fire. The town would be threatened by fire and engulfed in smoke long after we left. We eventually found clear air somewhere in Nevada. Massive fires in California have become unremarkable only to the extent they are increasingly common.

On the same trip home, we spent one night camped out on the banks of the Colorado River just east of Grand Junction, Colorado. The river looked more like a stream, seemingly lacking much flow, certainly not enough to meet the needs of the millions of people downstream relying on it. The West is in the midst of a 22-year megadrought and the river showed it.

The next day, we drove through Breckenridge, Colorado. As if to confirm our previous day’s observation, snow was virtually absent on the Tenmile Range overlooking the town. Snowmelt and rain from these mountains drain into tributaries that feed the Colorado River. Less water and early snowmelt seem to be a common occurrence in the Rockies these days. Perhaps I am remembering through snow-covered memories of my (Bob’s) youth spent in the Rockies, but I recall abundant snow on Colorado’s peaks throughout the summer months. Those days seem like a long time ago.

Let’s Try That Again

Which brings us forward to 2022. On our most recent trip to the Southwest this past spring, we delayed entering New Mexico by a day as winds up to 60 mph were tearing across the state. Multiple fires soon raged out of control in the northern part of the state for weeks afterwards, long before the fire season traditionally kicks into high gear. One fire, the Calf Canyon / Hermits Peak Fire, has become the largest in the state’s history and as of this blog date, is only 54% contained.

On the same trip, we once again visited the Colorado River, this time at Glen Canyon Dam in northern Arizona. The dam forms Lake Powell and its water is used by Arizona, California and Nevada. The water level has been dropping for years and is now down to dangerously low levels. When we visited, the water was down 177 feet, or roughly 76% from its full water mark as seen in the video clip below.

In the past year alone the water in the lake had dropped by 38 feet. Lake Powell and further downstream, Lake Mead, are drying up much faster than what had been forecast even one year ago. This not only means less water for homes and farms but also puts electricity (from hydropower) at risk for millions of households and businesses. On the positive side, many communities are significantly controlling their water consumption through conservation, innovation and infrastructure improvements. For example, see here, here and here.

Spotting a Trend

These are but a few indications of a changing climate we have witnessed the past few years. If you live in or have traveled out West, you no doubt have examples of your own.

Droughts and fires have always been commonplace in the West, and some argue our problems are primarily due to poor forest management or over-population in the naturally arid West, making normal events lead to outsized consequences. Or just the highly variable nature of the region’s climate. While these factors all seem partially true, they don’t tell the whole story – not by a long shot. A recent study by researchers at the Universities of Montana and Wyoming said the 2020 fire season in the Rockies was the worst in 2,000 years. Another study concludes the West is currently in its worst drought in 1,200 years.

What’s happening isn’t any cycle we are accustomed to.

When it Rains…

Because of our love for the West, traveling through it the past few years has been emotionally tough at times. Moisture is increasingly absent due to what is being termed the aridification of the West – rising temperatures creating a permanent dryness of the environment. Actually, this linked article refers to the aridification of North America. (Lest you think that is alarmist clickbait, check out this estimate of current and future wildfires in your zip code.)

It seems there is even less and less respite in the “wet” months. Of course, when the water does come back, it sometimes comes back with a vengeance, especially in areas where vegetation has been lost. One week to the day after we camped by the Colorado River in 2021, a storm rolled through the area and mudslides buried Interstate 70, due in part to the 2020 Grizzly Creek Fire clearing out vegetation that helped hold the soil in place. Mudslides are nothing new in the mountains, but highway engineers said the damage from this one was unlike anything they had seen before from previous mudslides.

We’ve been trekking West for well over fifty years, yet nothing prepared us for what we have experienced at times the last few years. Our hearts go out to not only the people and all the other creatures living under these conditions but also the land itself. The West is being squeezed dry.

Bob and Julia

Ps: We visited Glacier National Park last year and it was amazing. However, seeing photos from this site makes us wish we had visited the park well before the last century came to a close. What should Glacier National Park be called if and when most of its glaciers are gone?

Note: Header photo is of the Colorado River at Horseshoe Bend in Arizona, May 3, 2022.

You Might also like

-

A Common Vocabulary

Some words and ideas never seem to feel dated. They are as relevant and essential today as they were generations ago. Immigrants, young and old, tell us this.

-

Each Path is Worth Exploring

Whether it’s hiking a trail to see a majestic redwood or listening to someone answer the question we pose, each path is worth taking.

-

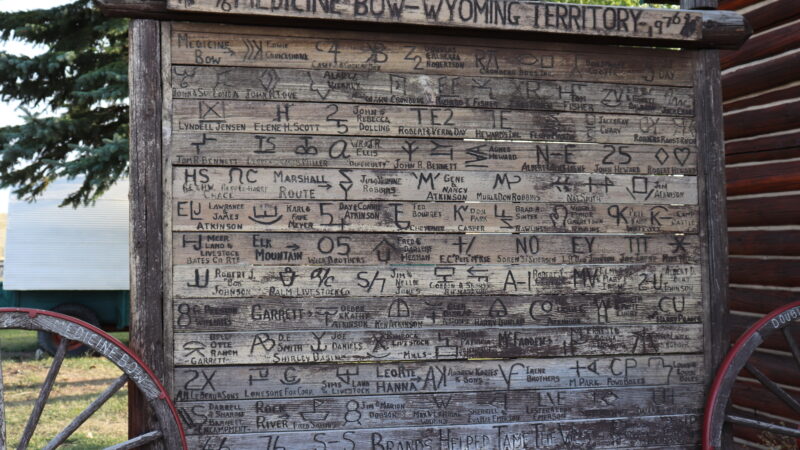

A Place. A Destination. Something Else?

West is such a simple word. Four letters, one syllable. And yet, it has a hard-to-define energy that dwarfs its brief length.