A Place. A Destination. Something Else?

January, 2022

From the Movie Last of the Mohicans (circa 1757)

Hawkeye: “Headin’ west to Can-tuck-ee.”

Major Hayward: “There is a war on. How is it you are heading west?”

Hawkeye: “Well, we kinda face to the north and real sudden-like turn left.”

So far, our van has rolled through 36 of the lower 48 states. All have offered numerous reasons for us to return. One can lose track of the days relaxing in the soft sands and warm water of the Gulf Coast. Or be immersed in the history, and beauty, throughout New England. Or experience a sense of contentment as picturesque farms in the Ohio Valley pass by.

But like the old horse that starts to trot a bit faster when headed back to the barn, our van seems to pick up speed when steered in a westerly direction. Is it the diesel engine or is it my right foot? Hard to say as both are energized by the highway underneath. I believe even a diesel van like ours has a big-truck heart, longing to hit the open road. And where are there more open roads than the American West? I can’t prove this theory, but it feels true.

Seeking West

What we’ve also come to believe is true is that the American West is more than just a place. After all, where is the “West”? The West seems to be unencumbered by defined boundaries, except for maybe the Pacific Ocean. Traveling from the sands of Florida to the tallgrass prairies of Oklahoma with its bison, one could say they have entered the West. And justifiably so. Yet, living in Oklahoma, Julia and I always look forward to pointing our van further westward and entering the mountain time zone. Feeling the air getting thinner long before we see the Rockies. Driving roads that rise up until they disappear into the big sky. Then when the storms roll in and the sky disappears, gaining a new-found appreciation for the absence of shelter in the West’s wide open spaces.

Looking West

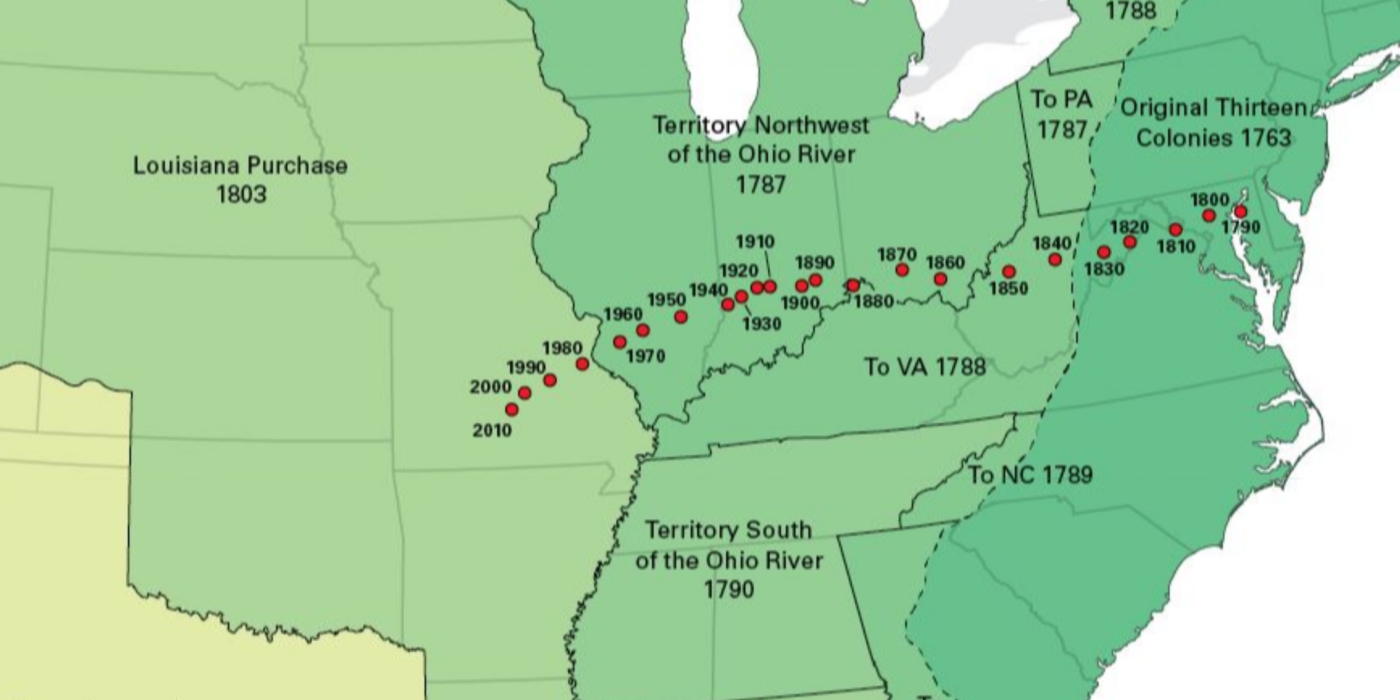

After a while, we’re visually grazing over maps somewhere else to the left of us. I suppose west was simply the necessary direction shown on our ancestors’ maps as they settled this land. In 1790, the newly created U.S. Census Bureau said half the population lived from the Atlantic Ocean to just east of Baltimore, a distance of less than 100 miles. The other half lived from Baltimore to what are now the states of Kentucky and Tennessee, as much as 700 miles to the west. So, by this measure, some might have viewed the West back then as everything to the left of the original 13 colonies. Plus, most of the continent still lay west of all this land – the vast unsettled West.

Exactly one hundred years later, the population center was now in Indiana and the Census Bureau announced there were no more unsettled frontiers from the Atlantic to the Pacific. We had run out of territory to discover. Sure, there was still (and is still) plenty of open land in the western states and territories. But if west meant unexplored terrain, the West was slowly shrinking. (Obviously, this government pronouncement and point of view were from the perspective of European-origin settlers as American Indians had not only explored the continent from coast-to-coast but had settled the continent for thousands of years prior to the Census Bureau taking its first count.)

Finding West

Today, if boundaries exist, I think they’re usually in the eye of the beholder, and subject to considerable debate. Even though it’s home to the amazing arch, is St. Louis really the “Gateway to the West”? Or should it be Kansas City? Or some other location? Is the Pacific Ocean even a hard boundary or does the American West border jump over to Hawaii?

And the boundaries can pop up in unexpected places. Here’s one for us: the middle of South Dakota where the Missouri River roughly divides the state in two (Google satellite image, below right). To the east are plentiful farms and ranches, admittedly with inhabitants who would likely say they live in the West. To the west of the river though is a change of geography, and with it, a changed mood traveling through. The highway is now walled in by craggy hills. More dry, open plains replace the green patchwork of east-side farms. The Badlands are still a ways off, but you now sense you are on the right trail.

As if to confirm something anew, on a tree-lined bluff high above the Missouri River’s eastern shores stands the statue Dignity of Earth and Sky, a 50-foot-tall sculpture of a Native American Woman (located at yellow dot on image, above right). It’s as if she is welcoming all to the American West – and to a different era. Our van has a renewed energy as it crosses the Missouri. At least, that’s how it felt to us.

Something Else

And it’s that feeling of something different that we recognize when we talk to people living out West. What America means to them, and their own identity, are often inextricably tied to the land and its history. As we listen to people explain this belief to us, we begin to think that maybe the West means something more than just a place or direction. Maybe it’s the embodiment of a spirit buried in us all, some more disrupted by it than others. And one that might take a lifetime to truly understand. Here are a couple short conversations with two people who recently wandered left and now call the West their home.

Cheers,

Bob and Julia

You Might also like

-

Wait Just a Darn Minute

We started out simply being amazed at the fast changing weather along our scenic route home. Then we began to wonder, maybe Mark was right all along. Or was it Will?

-

Heading West

If you haven’t felt the pioneer spirit of the West before you hit Sheridan, you certainly will as you drive into downtown with the Bighorns in the distance.

-

The Mailbox Paradox

The joy of travel: It’s not just about the excitement of arrival. It’s also about the relief of departure.